You leave home in the morning and go to the doctor. A robot offers you several possibilities for treatment based on your medical history, relating it to the most up-to-date methods and therapy. Then you go to the bank and another machine, based on accumulated data about your transactions and profile, offers you a loan, checks the data, and takes responsibility for all the procedures. You return home and your car, on the way, warns that you are tired and it is time to stop driving, to avoid an accident. If days later you return to the clinic and discover you need a transplant, the organ you will receive may be totally artificial, made up using chips. It seems like something from the movies, a science fiction reality; and even though they are cases of artificial intelligence, indicating the AI’s possibilities.

You leave home in the morning and go to the doctor. A robot offers you several possibilities for treatment based on your medical history, relating it to the most up-to-date methods and therapy. Then you go to the bank and another machine, based on accumulated data about your transactions and profile, offers you a loan, checks the data, and takes responsibility for all the procedures. You return home and your car, on the way, warns that you are tired and it is time to stop driving, to avoid an accident. If days later you return to the clinic and discover you need a transplant, the organ you will receive may be totally artificial, made up using chips. It seems like something from the movies, a science fiction reality; and even though they are cases of artificial intelligence, indicating the AI's possibilities.

One of the most important books on the subject is journalist Steven Levy’s Artificial Life: A Report from the Frontier Where Computers Meet Biology. The book deals with research involving the creation of artificial life, based on the intersection between genetic engineering and AI. What can be done and how far does this research go? Would we be moving toward creating an artificial kind of life just like HBO’s Westworld series?

The automotive industry was one of the first to use AI industrially after 1950, when British mathematician, Allan Turing, considered by many as the father of Computer Science, created the test named after him. Through this test, a machine could be considered intelligent if it could emit reactions equivalent to those of a human being. Technological evolution has led, for example, robots to produce and pack parts, with no manual contact. Currently, robots installed in cars compare the driver’s driving style in the first few minutes to warn them if they are tired. Banks also employ them to prevent fraud and to verify suspicious transactions. In medicine, Watson—launched by IBM in 2011—is used in hospitals, although not all of its functions, such as diagnostics, are applied yet.

“We live in a world in which many technologies and possibilities foreseen in the 1970s and 80s have not yet been materialized. This was a period of many lessons about what the new century and the new millennium would be like. Many other projects, however, have taken form and come into existence, although no one spoke about them or even imagined them. This is a challenge because it is not possible to know what will happen, no matter how many prognoses are made.

Technology and AI bring many possibilities and they are good for society, but something must not be forgotten: Science must have a dialogue with Ethics and Education,” explains Professor Pavlos Moraitis in an exclusive interview for 25th Century Magazine. He works at the René Descartes University in Paris, France, that has a postgraduate program in AI. Since the early 1990s, Moraitis has been reflecting on, and supervising, work on technological advances and the relationship between power and ethics. He currently runs the university’s computer research lab.

As there is no Cartesian logic in the development of AI, these concerns also involve advancements enabling interaction between machines. As AI advances and robots can do human activities, machines—just like people—are also engaging in ethical arguments and even crimes. In 2011, as reported by a number of publications such as Reuters, a drone from the United States killed a group of men in Pakistan, interpreting as “suspicious behavior” a small crowd trying to resolve a local conflict.

The United Nations said in a 2014 document signed by Ben Emmerson—rapporteur for the promotion of human rights in the fight against terrorism—that the data on deaths from drones are not transparent. The report on armed drones calls for greater transparency and accountability deals with issues involving the legality of actions and the risk they pose to international law.

Artificial life

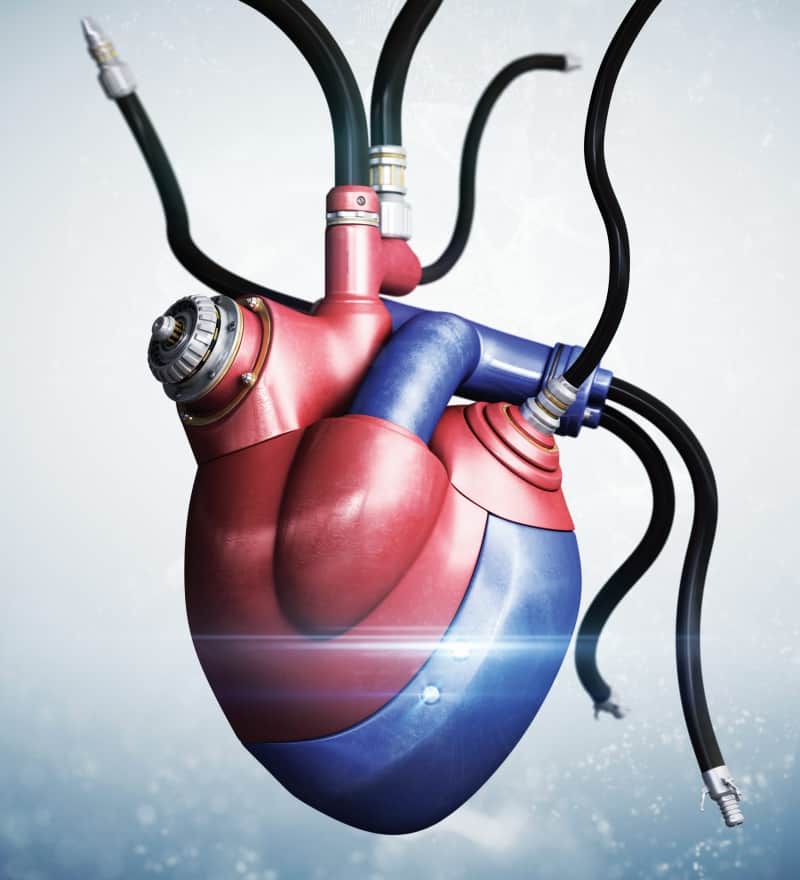

All the news and possibilities of advancement toward artificial life increase controversy and concern. They become much clearer when even parts of the human body are recreated. At Harvard University, researchers have managed to produce kidneys, liver, and bone marrow using AI. The next step is connecting all these parts to a chip, which —when everything is integrated—can form a complete organism. For now, the idea is to use the system for drug testing, which will not require guinea pigs anymore. In another step, however, the production of life-size organs is planned for use in transplants.

Image from istock.com

Image from istock.com

As these artificial organs try to reproduce human features and functions, such as cellular maintenance, it is expected that we’ll be able to see how treating one part of the body would affect another in the event of drug intervention. The positive aspect is that this can aid in the development of more effective drugs with fewer side effects. With the production of marrow bones, for example, it is possible to see a glimpse of the creation of artificial blood, which is also being researched with early satisfactory results at the University of Massachusetts, in the United States. The point is that, even before the technology is tested and finalized, the U.S. Department of Defense, in the Pentagon, has made it public that they fund this type of research to connect artificially created members, giving rise to androids developed in labs, corroborating the thesis on artificial life. Pentagon scientists acknowledge that lungs and a liver were produced, each one a little more than eight square centimetres.

The supposed reason for creating them is the possibility to test these organs and the technology involved to treat people wounded in war, including those struck by biological or chemical weapons. This does not fail to remind us of what until recently was seen only in movies, like in the story of Robocop (1987), directed by Paul Verhoeven. When an agent suffers an accident, his organs are replaced by a technological system, leading to the first android police officer in history.

“It is claimed that these organs serve for drug testing, but the question is just how far that can go. Both the legislation and the constitution of ethics on the subject are still lacking, because, in general, we separate what it is to be human and what it is to be artificial. However, I believe that today we shouldn’t focus too much on this separation, but rather on how far this integration can go. What is at stake is not artificial intelligence, but its relation to humans,” argues Professor Moraitis.

Image from istock.com

Image from istock.com

Engineer, Isabela Ramos Vitorini, recently returned from the USA where she obtained a master’s degree in computer science at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania, with studies in the area of computer–human interaction. Note that the order is not “human–computer”, as she is keen to point out. “Without even realizing it, we have such naturalized interaction in so many areas that we don’t even perceive it. Look at how we use mobile operating systems and how algorithms determine our choices. It is not only us, humans, who consult them, in an attitude in which technology is passive; they tell us how to act and what to consume.

Moreover, some technologies like pacemakers and prostheses have been successfully used for a long time. I believe in the potential of all this; it all looks positive. I do not have a dystopic point of view. I believe that, just as we have learned to gradually use the technology available today, we will learn to use the technology of the future. The benefits outweigh the problems. We just need an education that considers these issues,” she explains. The researcher also reminds us that prosthetics that use AI make it possible to read nerve impulses and provide human beings with activities that can range from simply walking to high performance activities, as in the case of Paralympians, as we call them today. Evolution could end such differences, but it will be necessary to discuss limits, because the human body has limitations that machines will not need to have.

Education

Since artificial life—which also has AI—is emerging in research institutes, it could also replace some of these scientists in one of the tasks that usually accompanies their work: teaching. Jiujiang University, China, for example, has already held classes taught by a robot teacher, called Xiaomei, created by scientists from the Department of Computer Engineering and Intelligent Robotics of that institution. The prototype took a month to launch. During the test-lessons, the “teacher” used PowerPoint presentations and was able to undertake short interactions with the students—even answering questions. Xiaomei continues to be used, even with limitations such as the need to standardize the commands students use to communicate with it.

With these problems in mind, the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP) created a continuous course aimed at discussing the implications of the relationship between human beings and AI. The course, “Artificial Intelligence: Conceptualization of Technology and Social Impacts” is coordinated by professor Lucia Santaella, internationally recognized as one of the main references in Semiotics. The course aims to discuss relationships between human and artificial intelligence and how this could impact cognitive functions. The aim is also to reflect on how new talents are needed in this area.

As a member of a group named “Transobjeto”, Santaella has dedicated herself to reflecting on technological contemporaneity, the function of technical objects, the Internet of Things, (IoT), and the relation of these elements to language. In the article, “AI has come to stay, grow, and multiply”, Santaella explains that “judging by its recent advances, there is little doubt that, sooner or later, AI should encompass many of the skills we have so far considered to be exclusive to humans.” And it is at this point when, according to the author, two warning signs appear.

The first is about how technological growth can be explained in a deterministic way; that is, we deal with it based on the assumption that technology drives the development of social structure and cultural values. Although the term and discussion began in the early twentieth century, as we can observe in the work of economist Thorstein Veblen, this conception continues to gain followers. From this point of view, it is also believed that the development of technology has a predictable and traceable path.

“At no stage of evolution have humans been dependent on nature or instincts alone. There is no dichotomy between nature and culture, because human society has been formed in the gradual artificialization process of the world,” writes Santaella. She adds: “Current generalized cyborgization is nothing more than the ineluctable continuation of humans’ departure from nature in the construction of other artificial natures. Moreover, nature has always shown a malleability of the artificial; therefore, the boundaries between nature and culture, organism and machine, have to be continually redrawn in accordance with complex historical factors”.

The second warning sign raised by the researcher is that the undeniable growth of intelligence can be historically proven. “However, it would be risky to pass a value judgment tending to euphoria on such a postulation. Although AI can indeed facilitate and increase human tasks and improve the services provided by corporations and governments, there is a field there that deserves and requires to be treated with care and with ethical precautions. “Artificial intelligence, like any other technology, is not beyond human intelligence. This, far from being nourished by pure reason, is overdetermined by the unconscious”, argues the semioticist.

An important point raised by Santaella is the fact that we must not fail to speak about AI and, consequently, about artificial life, without forgetting that it is fruit of human experience, placing it within limits and day-to-day concerns, with attention to uses as a political or biological weapon. In indicating the possibility of artificial life, science makes it even more necessary to debate and approach this issue in education, at all levels.

by Fabiano Ormaneze

Language Quality Assurance Reviewer

Albina Retyunskikh